Description

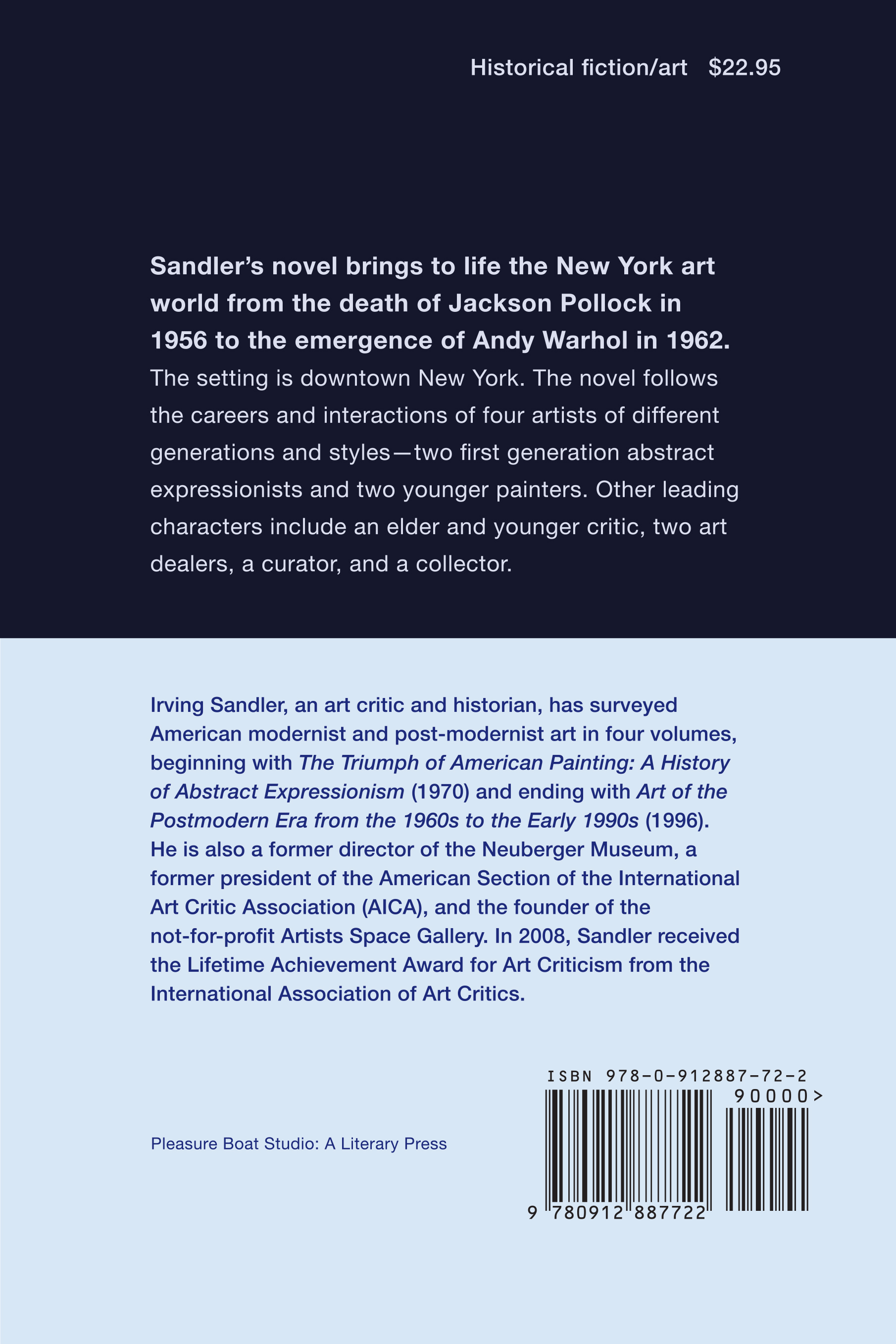

Irving Sandler brings to life the New York art world from the death of Jackson Pollock in 1956 to the emergence of Andy Warhol in 1962. The setting is downtown New York. The novel follows the careers and interactions of four artists of different generations and styles—two first-generation abstract expressionists and two younger painters. Other leading characters include an elder and younger critic, two art dealers, a curator, and a collector.

The novel portrays competition within the self and with others for artistic recognition, as well as the soul-searching suffering for one’s art. Connections are forged and betrayed. Whether relationships thrive or plummet, for business, pleasure or both, makes for an exciting, tough and dramatic world. Art theory and art history are interwoven throughout this crisp and sparkling narrative.

Irving Sandler, an art critic and historian, has surveyed American modernist and post-modernist art in four volumes, beginning with The Triumph of American Painting: A History of Abstract Expressionism (1970) and ending with Art of the Postmodern Era from the 1960s to the Early 1990s (1996). He is also a former director of the Neuberger Museum, a former president of the American Section of the International Art Critic Association (AICA), and the founder of the not-for-profit Artists Space Gallery. In 2008, Sandler received the Lifetime Achievement Award for Art Criticism from the International Association of Art Critics.

From ARTnews: “‘The thread that runs through my writing is a concern for the intentions, visions, and experiences of artists,’ the art critic and historian Irving Sandler wrote in 2006. He was looking back on a career that tracked the art of half a century, from Abstract Expressionism to the constellation of styles and approaches that constitutes the art of the early 21st century. Sandler, who passed away earlier today at age 92, never stopped looking, and thinking. The Philadelphia-born Sander started his career as an art critic in 1956, in the pages of ARTnews, where he became a regular reviewer. Thomas Hess was editor at the time. He went on to write reviews for the New York Post and Art in America.”

REVIEW QUOTES:

From The Wall Street Journal: “A lively novel of the Abstract Expressionist art scene that is everything you’d expect from critic Irving Sandler, who seemingly befriended every painter, writer and dealer in 1950s New York….As a critic for Art News and the New York Post, he profiled so many notables that Frank O’Hara called him a “balayeur des artistes” (or “sweeper-up after artists,” a phrase Sandler borrowed for the title of his memoirs). His novel is as lively an account of its milieu as you’d expect from its famously gregarious author…We begin in 1963, just as kitschy, frothy Pop is replacing Abstract Expressionism as America’s definitive art movement…full of drama and intrigue…” – Jackson Arn

From New Criterion, Art: “If Irving Sandler (1925–2018) had been Japanese, he would have been declared by his people a “Living National Treasure.” From the 1950s to his death, he was a crucial figure in the evolving story of American vanguard painting and sculpture: a friend of artists and frequent studio visitor, director and founder of alternative galleries, art critic, professor of art history, museum director, and, above all, witness and chronicler of the changing desiderata of the moment…Goodbye to Tenth Street is a must for anyone interested in an art world very different from today’s. Sandler immerses us in a time when artists sought aesthetic excellence, intensity, and—above all—individuality, striving to charge their work with their entire being rather than “strategizing.” (Except for the novel’s venal Neil Johnson.)…aesthetic values…were life-and-death matters, to be wrestled with in the studio and, elsewhere, to be argued about, challenged, fought over, and even died for. Sandler vividly recreates the atmosphere in which such beliefs flourished. For facts, The Triumph of American Painting and The New York School are still essential, along with his two volumes of memoirs, with their privileged information. But for sheer entertainment, go to Goodbye to Tenth Street.“ – Karen Wilkin

From Midwest Review: “Showcasing Irving Sandler’s impressive narrative driven storytelling talents as a novelist, “Goodbye to Tenth Street” is an inherently fascinating and skillfully presented read that ably conjures up a kind of ‘window on the past’, making it very highly recommended for personal reading lists, as well as community and academic library Literary Fiction collections.”

From The New York Times / Best Art Books of 2018:

Roberta Smith ~ NYT: The BEST ART BOOKS of 2018 |

‘GOODBYE TO TENTH STREET: A NOVEL’ By Irving Sandler (Pleasure Boat Studio). Anyone drawn to the postwar art scene that centered on Manhattan’s East 10th Street should read the last book of Mr. Sandler, the art historian and critic extraordinaire who died in June. He was there in the late 1950s and early ’60s taking notes while the Abstract Expressionists made history, and he became known for his meticulous accounts of their saga. But here he offers a roman à clef filled with the unverified gossip, overheard conversations, and rumors of nooners and backbiting that were unsuitable to fact-based history (though a few historical figures occupy the margins). The tale — from charged studio visits to nasty exchanges at the Cedar Bar — has its own sad, sordid, unsurprising truth. |

TRIBUTES: Remembering the deeply inspired, influential and respected Irving Sandler

The Art Newspaper: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/remembering-irving-sandler

NY Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/02/obituaries/irving-sandler-dead-art-critic.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/13/arts/design/best-art-books-of-2018.html

Brooklyn Rail: https://brooklynrail.org/2018/07/in-memoriam/A-Tribute-to-Irving-Sandler

Apollo Magazing: https://www.apollo-magazine.com/irving-sandler-obituary/

Book and cover design concept by Catherine Sandler, Irving Sandler’s daughter, who was also a copy editor along with Jack Estes, main editor. Design production by Lauren Grosskopf

Jack Estes, Former Publisher and current primary editor –

Goodbye to Tenth Street is the first novel, after a long writing career, by Irving Sandler. Clearly Sandler knows how to penetrate the depths of the art world in the U.S. throughout the 50’s and 60’s. Sandler explores the business and the culture of artists, including the alcohol, the sex, and the deep competitions. Artists, critics, gallery owners – everyone has a role in this terrific novel.

Lauren Grosskopf, Publisher –

When Irving Sandler ran the Tanager Gallery on 10th Street in the East Village, as well as coordinated the artists’ club from ’55-’62, he began observing and delving into the personal, historical and philosophical contexts and reasons behind the artists and their art, which he viewed in galleries and museums all across Manhattan. He was not of the variety to critique only visual formal attributes. He documented conversations from the Cedar Street Tavern as well as other artists’ venues. He began writing art criticism for ARTnews which set him on a path to become a prominent art critic and art theorist, publishing several books. He will always be remembered as a critic for the artists, for the people, with many friends and very few enemies.

“The thread that runs through my writing is a concern for the intentions, visions, and experiences of artists,” the art critic and historian Irving Sandler wrote in ARTnews in 2006. This crisply written novel is a prism for a story that alights a bygone era. This is a cultural gift to American art history – a studied look at the breakthroughs of abstract expressionism and the beginnings of pop art – and makes us ponder the pursuit for meaning, emotional honesty and objectivity via artistic expression.

Everett Aison, author of ARTRAGE –

During the Post War years of the 50’s and 60’s, New York City emerged as the epicenter of Western Art.

It’s brilliant painters, gallery owners, art critics, and collectors became intertwined, sharing a Manhattan rooftop water tower filled to capacity with intellectual self-doubt and sexual neurosis.

In “Goodbye to Tenth Street”, Irving Sandler ,life long Humanist and expansive/insightful critic, takes you gently by the elbow into the Cedar bar. The rest is up to you.

Roberta Smith, The New York Times, The Best Art Books of 2018 –

‘GOODBYE TO TENTH STREET: A NOVEL’ By Irving Sandler (Pleasure Boat Studio). Anyone drawn to the postwar art scene that centered on Manhattan’s East 10th Street should read the last book of Mr. Sandler, the art historian and critic extraordinaire who died in June. He was there in the late 1950s and early ’60s taking notes while the Abstract Expressionists made history, and he became known for his meticulous accounts of their saga. But here he offers a roman à clef filled with the unverified gossip, overheard conversations, and rumors of nooners and backbiting that were unsuitable to fact-based history (though a few historical figures occupy the margins). The tale — from charged studio visits to nasty exchanges at the Cedar Bar — has its own sad, sordid, unsurprising truth.

Karen Wilkin, New Criterion, Art February 2019 –

Irving Sandler’s goodbye by Karen Wilkin

On the legendary art critic, scholar, and museum director, who died in 2018.

If Irving Sandler (1925–2018) had been Japanese, he would have been declared by his people a “Living National Treasure.” From the 1950s to his death, he was a crucial figure in the evolving story of American vanguard painting and sculpture: a friend of artists and frequent studio visitor, director and founder of alternative galleries, art critic, professor of art history, museum director, and, above all, witness and chronicler of the changing desiderata of the moment. When Sandler died in June, a few weeks short of his ninety-third birthday, the art world lost a legend. Until the very end of his long, busy life, he was a seemingly ubiquitous presence who knew or had known everyone, tirelessly attending exhibitions, panels, and lectures, taking exhaustive notes in his tiny handwriting and asking probing, informed questions. The four volumes that bear witness to his experience—The Triumph of American Painting: A History of Abstract Expressionism (1970); The New York School: The Painters and Sculptors of the Fifties (1978); American Art of the 1960s (1988); and Art of the Postmodern Era: From the Late 1960s to the Early 1990s (1996)—together provide a history of (mostly) American art after World War II. Required reading for several generations of scholars and collectors, and equally fascinating for those with even a casual interest in the subject, these books are notable for their deep, firsthand knowledge and their jargon-free, lucid prose.

… The main character in Goodbye to Tenth Street, the painter Peter Burgh, for example, seems like an amalgam of Mark Rothko and Philip Guston (absent Guston’s last, fierce, politically charged figurative phase), to judge by Sandler’s descriptions of the evolution of Burgh’s work, from early Social Realism to lyrical abstraction for which he was recognized and admired, followed by a transformed, less popular last series. An influential female art dealer, Celia Loeb, shares the sexual appetite attributed to Peggy Guggenheim, while the artists she exhibits remind us of those supported by the less flamboyant Betty Parsons…

Goodbye to Tenth Street is a must for anyone interested in an art world very different from today’s. Sandler immerses us in a time when artists sought aesthetic excellence, intensity, and—above all—individuality, striving to charge their work with their entire being rather than “strategizing.” (Except for the novel’s venal Neil Johnson.) Recognition and sales were, obviously, desirable and welcome, but in contrast to the present day, aesthetic values, rather than monetary worth, were life-and-death matters, to be wrestled with in the studio and, elsewhere, to be argued about, challenged, fought over, and even died for. Sandler vividly recreates the atmosphere in which such beliefs flourished. For facts, The Triumph of American Painting and The New York School are still essential, along with his two volumes of memoirs, with their privileged information. But for sheer entertainment, go to Goodbye to Tenth Street.

Jackson Arn, The Wall Street Jounal –

‘Goodbye to Tenth Street’ Review: A Final Sweeping

A lively novel of the Abstract Expressionist art scene that is everything you’d expect from critic Irving Sandler, who seemingly befriended every painter, writer and dealer in 1950s New York.

By

Jackson Arn

Feb. 15, 2019 9:41 a.m. ET

Irving Sandler’s novel “Goodbye to Tenth Street” is set in a faraway world where tavern-goers sit around all night without buying anything, Jackson Pollock or Andy Warhol is always somewhere at the party, and up-and-comers say things like, “There’s a philosophy I find meaningful called Existentialism”—in short, lower Manhattan in the 1950s and ’60s.

It would be no exaggeration to say that Sandler, who died last year at the age of 92, knew this world better than anyone. His passion for art began, by his own account, with a chance viewing of Franz Kline’s “Chief” at MoMA in 1952. By the middle of the decade he had befriended Kline, along with seemingly every other painter, writer, curator and dealer in the city, and become the manager of Tanager Gallery, a pioneering artist collective located, like so many of the key galleries of the era, on Tenth Street. As a critic for Art News and the New York Post, he profiled so many notables that Frank O’Hara called him a “balayeur des artistes” (or “sweeper-up after artists,” a phrase Sandler borrowed for the title of his memoirs). His novel is as lively an account of its milieu as you’d expect from its famously gregarious author, but liveliness can’t always make up for stick-figure characterization or flat-footed prose.

GOODBYE TO TENTH STREET

By Irving Sandler Pleasure Boat Studio, 359 pages, $22.95

We begin in 1963, just as kitschy, frothy Pop is replacing Abstract Expressionism as America’s definitive art movement. One casualty of the changeover is Peter Burgh, a once-promising AbEx painter found dead in his studio with a pistol in hand. Like most of the novel’s cast, Burgh is a patchwork of real-life people: a pinch of Mark Rothko (alcoholism and depression), a touch of Philip Guston (early years as a muralist), perhaps a little of Sandler himself (service in World War II).

Burgh’s artworks, romances, rivalries and friendships in the seven years leading up his suicide form the backbone of “Tenth Street.” “Abstract Expressionism,” his obituary reads, “is the triumph of American painting, and in large measure, its stature depends on Burgh’s paintings.” The giveaway phrase there is “the triumph of American painting,” also the title of Sandler’s influential study of American art after World War II. What we’re being promised, then, is a gossipy retelling of a story the author knows well, full of drama and intrigue and barely disguised versions of his friends and enemies.

Though it sounds strange to say about a man who loved getting to know people, Sandler struggles to write interesting characters. The user-friendly style that made him a lucid critic and a beloved professor is too didactic for fiction—he rarely uses indirect discourse, or any other novelistic technique for that matter, to get inside his creations’ heads. When someone talks, it’s often to parrot Sandler’s ideas, qualified with a phrase like “Sounds pretentious, I know, but . . .” The result is that, of the dozens of speaking parts in this nearly 400-page book, only Burgh’s lingers in memory, and even his is cheapened by a lame Freudian backstory involving a dead father and a bad day at Guadalcanal. It is typical of the author’s schematic, sometimes cringey approach that this backstory is whispered in post-coital installments seasoned with devil-may-care comments about “what Siggy Freud would make of that.”

Sandler fares better when he turns to the frank, material side of the art world. He’s entertainingly tough on his own profession: When a tastemaker named Marshall Hill (who sounds suspiciously like Clement Greenberg) prattles on, young artists listen, since they know his praise can double the price of their paintings. Other critics write rave reviews to boost the value of their favorite curators’ collections or invent movements out of thin air to have an excuse to travel for free. This is a novel of receipts, bills, loans, interest rates and sunk costs—not since Balzac have characters talked about money with so much dull lust.

Like Balzac’s “The Unknown Masterpiece,” the fable on which Burgh models his suicide, “Tenth Street” doesn’t entirely reveal whether the artworks it describes are great or second-rate. The Tenth Street scene of the late 1950s and early ’60s is often remembered as a faint echo of the Abstract Expressionist boom immediately following World War II, too obsessed with imitating Pollock and Kline to surpass them. This isn’t necessarily bad news for Sandler, who, whatever one thinks of his fiction, was one of the key American art critics of the last century. Whenever his novel strains to convey misty-eyed genius, it falters, but it can be charming when dealing with the less-than-great. That may sound pretentious, but it’s true.

—Mr. Arn is a critic, poet and filmmaker living in Brooklyn, N.Y.

Thalia T –

I lived there during that time, studying art history and interested in the art world. It really paints a good picture of what it was like in the NY art scene in the late 50’s / early 60’s.