Description

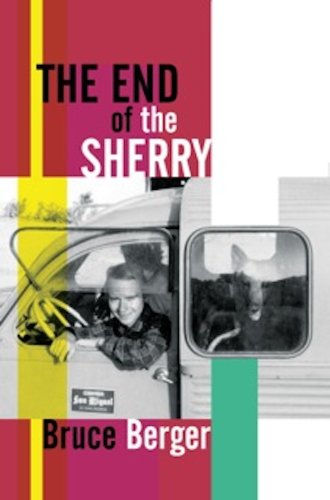

Literary Nonfiction. Memoir. LGBT Studies. THE END OF THE SHERRY recounts what happens to a young American who finds himself abandoned in southern Spain in 1965 with a dog and a dubious car, who stumbles into work as a nightclub pianist and stays for three improbable years. His own adventures blossom into a portrait of provincial Spain toward the end of the Franco dictatorship—bleakness that breaks into unexpected hilarity even as the author discovers his calling as a person and a writer. His return to Spain after the death of Franco puts it all into perspective.

The End of the Sherry won the 2014 Silver Medal for the most outstanding nonfiction book of the year awarded by the Independent Publishers Association.

Chosen as an Indie Ground Breaking Nonfiction

Read about The End of the Sherry in the Aspen Times.

“Raucous adventure transpires… Berger writes richly and animatedly about the people he met, the places he explored, the spiritual subjects he parsed, and the unforgettable experiences he lived to the fullest during his time in Spain… Berger’s dynamic and lively prose, proves thoroughly infectious…” –Craig Manning, Independent Publisher Magazine (Read the entire interview)

A kinetic memoir… an engrossing adventure.

Lovely anecdotes follow one after another, a connoisseur’s selection painted with specificity and a bright palette. When Berger wrestles with the meaning of cachondeo, he defines the picaresque nature of his own existence. —New York Journal of Books

Bruce Berger, www.bruceberger.net, is an award-winning nonfiction writer and poet of ten books, best known for his works exploring the intersection of nature and culture, usually in desert settings. Those works include the essay collection THE TELLING DISTANCE: Conversations with The American Desert (winner of the 1990 Western States Book Award for Creative Nonfiction and the 1991 Colorado Book Award); THERE WAS A RIVER, its title piece a narrative of what was probably the last trip on the Colorado River through Glen Canyon before its inundation by Lake Powell; and ALMOST AN ISLAND, which recounts three decades of exploration and friendships in Baja California. His desert writing has been widely anthologized. Mr. Berger’s recent book is OASIS OF STONE, in collaboration with award-winning photographer Miguel Angel de la Cueva. “A knock-out look at Baja California Sur” The San Diego Union-Tribune. Winner of the 2006 ForeWord Silver Award for nature writing.

Tom Eubanks –

During the three years he spent on the Iberian Peninsula in the mid-1960s, Bruce Berger encountered the following joke: “If Franco is at the helm, the Guardia Civil is on the prow, the priests are on the poop and the ship sinks, who is saved? Spain.”

Those who lived under decades of fascist dictatorship shared this kind of gallows humor, once they had run out of absurd anecdotes from the Generalissimo’s personal life. Berger points out the joke’s cruel irony when he returns to post-Franco Spain and finds a torn social fabric, rife with barbarism and drugs. “The dog has died but the rabies lives on,” observes an old friend, Manolo.

Despite its title, The End of the Sherry is not strictly a book about sherry–although many copas are consumed and many tidbits of trivia are shared. The word “sherry,” for instance, is a crude English derivation of the town of Jerez, one of the drink’s key producers before the end of Franco.

Although there’s plenty of travel, Berger doesn’t consider his book travel literature. Following one of his literary idols, Lawrence Durrell, Berger aims instead for a “residence book.”

“In this kind of book,” he explains, “one didn’t need to invent characters and put them through their paces; you simply soaked up what was around you, then extruded it into prose.”

Through a series of picaresque characters and fortuitous events, Berger and his dog, Og, in their illegally registered Citroën, affectionately called “the Lung,” circumnavigate the country before settling between the “two Puertos”: Puerto Real and El Puerto de Santa Maria, around the Bay of Cádiz. Among sherry-drinkers, closet rockers, harassment from the Guardia Civil, and unending bureaucracies, Berger uses his talent for music to find work in a number of traveling bands. At one point, he recounts an especially unappealing stint as a fishmonger. He served as part-time English instructor and translator to locals and provides a chapter on the nuances of Spanish, the people and their language. His friendship with a man called “Sparkplug” leads to a bitter description of being a pawn in the brutal Civil War that led to Franco’s 36-year reign.

A perfect illustration of the bureaucratic absurdities of life in Franco’s Spain comes just before the author returns to the United States, when the Lung is confiscated. Although Berger took the necessary and costly procedures to become a licensed driver in Spain and made certain to cross the country’s border “every six months,” as required by law–into Portugal “under its own dictator,” Oliveiro Salazar–the author’s “Yankee upbringing balked at paying a full third of the car’s original cost for a mere license plate.” Subsequently, a Cádiz court forced him to relinquish this last bit of freedom.

Woven throughout Berger’s memoir, keen readers may detect an elliptical, or outright chaste, relationship with a fellow band mate named Ramón. The first indication of an attraction comes when one suggests the other wear his underwear. Berger refers to Ramón as “complicado,” “the other half of my split existence,” and “bilingual and then some.” Asked by other friends what the two speak when alone, they answer, in unison, “French.” Later, when sharing a “not-quite-private room” in Ramón’s family home, the two engage in “pillow talk.”

Eventually, the couple touch during a street fair in El Puerto: “Ramón and I had our arms over each other’s shoulders while holding our free hands in front, a position that had to be mastered to navigate a sidewalk, but we were no different from other pairs of young men and young women …”

When Berger’s U.S.-bound plane lifted off from the runway in Sevilla, he “looked down and saw the lone figure of Ramón standing outside the terminal, gazing up at the plane.”

“My heart was breaking,” he writes, which comes as a surprise because the author refuses to share how intimate or invested he was with Ramón–and the only desire Ramón had for Berger was to control him.

One can understand the author’s hesitation to be open and honest about the details of his connection to Ramón while the two were living under Franco, but in 2014, it feels strange to have to read between the lines or decipher subtle innuendo to follow a love story.

But then, Berger’s memoir isn’t called The End of Ramón. Or, The End of Franco. Or, Gay Sex in Andalucia, for that matter.

In the end, it is Andulucían’s most notable intoxicant that inspires Berger to be lyrical and profound.

“[I]t was the collapse of sherry drinking that most stunned me,” writes Berger of his return to a democratic Spain. The leading sherry maker of El Puerto de Santa Maria no longer made sherry. The hangout in which the author discovered a “copious selection of sherries had been reduced to a token barrel, retained for atmosphere.” The wife of an old friend confessed that she drank her sherry cut with soda.

“The hallowed beverage turned into a spritzer?” the author asks incredulously. “It felt as if Spain itself were being phased out.”