Description

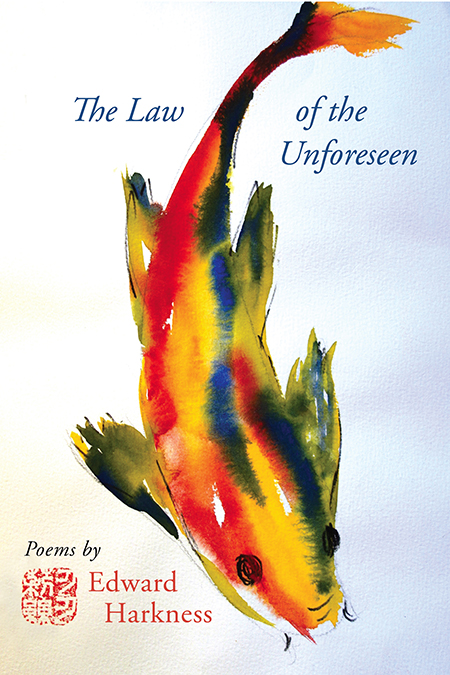

The Law of the Unforeseen is about family, history, family history, the natural world—its beauty, its degradation—the strange miracle of consciousness. I write about the blues, failure, great apes, time passing, icebergs, massage therapy, the Civil War, crows, bats, potatoes, spoons, and drones. Nothing is off the table. In fact, everything is on the table, including the fabled kitchen sink. (Front and back cover art by Doris Harkness, his mother).

The poet Galway Kinnell once said that when writing a poem, the deeper you go inside yourself, and the more intimate you become in the process of composing and engaging language with your whole being, a strange thing happens. The poem, Kinnell said, becomes both personal and universal. By diving deep, the poem discovers—or uncovers—what binds us, what we all feel: the quickened heart of recognition and shared emotions. That’s what I’ve aimed for in The Law of the Unforeseen: to plumb deep, to find “the best words in their best order,” as Samuel Taylor Coleridge said in his famous distinction between prose (“…words in the best order.”) and poetry (“…the best words in the best order”).

“In the poems of The Law of the Unforeseen, Ed is still showing that enthusiasm for entering wholeheartedly into whatever life he finds around him…Maybe what strikes me most about this collection is not only its ability to enter so empathetically into both the joys and the sorrows…but to insist on the power of just keeping on keeping on in the face of despair about the current condition of our war-ridden, climate-threatened, frustrating world. When I mentioned this to Ed, he pointed out how poets believe so strongly in the power of words to save us. That belief crops up often in these poems.” – Sibyl James, terrain.org

To his everlasting regret, Edward Harkness did not see Elvis when the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll visited Seattle during the World’s Fair in 1962. Other than that, Harkness is a happy husband to Linda, father to Ned and Devin, and grandfather to Clio and Hilde. Having retired after a 30+ year career as a writing teacher at Shoreline Community College, he now devotes his time to other pleasures: gardening, cycling, visiting the kids and, now and then, making poems. He is the author of two other full-length poetry collections, Saying the Necessary and Beautiful Passing Lives, both from Pleasure Boat Studio. His most recent chapbook, Ice Children, was published by Split Lip Press in 2014. Two poems in this collection, “Tying a Tie” and “Airborne,” won the Terrain.org annual poetry prize for 2017. He lives in Shoreline, Washington, about a mile from the north Seattle home where he grew up, and where his mother, Doris Harkness, whose art works grace the covers of this book, still lives.

Other PBS books by Edward Harkness: Beautiful Passing Lives, Saying the Necessary

INTERVIEW WITH SPLIT LIP PRESS MAGAZINE ‘He is the man, myth and legend, folks––Ed Harkness, runner-up of the Split Lip Press 2014 Uppercut Chapbook Awards’ Article on poetry process, open minded reflections on what makes a poet a poet, the development as a youth to love of sound and language, and what a beginning poet can do to grow as a poet.’

An interview with Ed Harkness by Wenatchee radio talk show host, Michael Knight:

Audio Player________________________________________________________________________

Poem from The Law of the Unforeseen

Honeymoon

A delirium of blossoms, he recalled.

Here we are on the bank of the Huzo,

walking in pink snow.

They were Americans, in love with love,

spellbound by pictures of Mount Fuji

they’d seen in National Geographic.

And there it was, appearing at sunrise

on the train window. How about that,

he’d said, waking her. It seems to hover.

It’s a vision, a floating island,

a perfect cone, just like the photos—

so symmetrical, so ideal, darling, like you.

In Kyoto, the river glided,

bright as mica, tinged with glacial till.

All the city, it seemed, had come to savor

the soft explosions of cherry trees,

just as they had come, these newlyweds,

arriving in a rickshaw, crowding with others

onto boats poled by young men

whose tanned arms glistened in April sun.

Then, excursions to temples and gardens,

where the azaleas had just begun to ignite

among the Zen stones. Such tranquility,

he told her on a stroll. Such harmony

with the natural world, don’t you think?

You won’t find that back home.

They even made love in a bamboo grove,

he remembered, thinking at the time

they were alone, with only the calls

of the different birds high in the green light,

then noticing as she rolled off him onto the moss,

her skirt askew, they were being watched.

An old woman in a conical hat smiled.

They smiled, mortified, unable to answer

the woman’s slight bow and greeting: Konnichiwa.

So long ago it was, that afternoon in the city

of pagodas and monuments, markets thronged

and rich with smells they’d never smelled.

Now, for Christ’s sake, they want to try out

the new bomb—Fat Boy, or Fat Man, or something—

on Kyoto, our Kyoto, where we climbed above the river

to that temple. What was it called? She wept, even,

when statues of the Buddha would appear

as if by magic, like sudden awakenings, among the pines.

He could imagine the shrines flattened,

ancient timbers blown to kindling by the blast,

the curved black roof tiles of ten-thousand buildings

swirling in typhoons of white fire.

Our city, for God’s sake. Our city.

Even the ice-fed Huzo would boil,

its boats aflame by the collapsed bridge

they’d walked across a dozen times,

and the young men who poled the boats—

they’d be burned to death in seconds.

So charmed the couple had been, so taken

by the politeness of the bowing Japanese,

so delighted were they when,

pulling their phrasebooks from their rucksacks,

they’d stutter a few words to a shopkeeper

or a woman planting rice shoots

along a road, and be understood.

He would demand that the committee

remove Kyoto from the list of targets.

Surely there were other cities more suitable

from a military standpoint,

more appropriate strategically.

What about Kokura’s munitions plants?

What about Yokohama or Hiroshima?

No matter what General X said or what General Y

argued would be the Emperor’s next move,

no matter what logic or tactical line of thinking

they’d array on their table of maps,

damage projections, casualty estimates,

he’d hold the line. He would not stand by

to see Kyoto—their Kyoto—

reduced to miles of radioactive ash.

The bomb, he vowed, would be dropped,

just not on the city he loved, his Kyoto.

His decision would be final.

Was he or was he not Secretary of War?

He’d go to Truman, if necessary,

get the full backing of the President.

Not one Shinto shrine, goddamn it.

Not one Zen pavilion. Not one pond of koi,

not one boy—I see him plain as day—

little canvas knapsack on his back,

riding his rickety bike to school,

pausing on the bridge to cover his ears

against the howl of air raid sirens.

I see him turn for home at the instant

the sun comes down to earth, flowering

like God knows what—a rose, a death rose

of heat and fire. No, no and no.

Not in Kyoto. Not in our Kyoto.

They’ll have to add another city to the list.

[Author’s note: Henry L. Stimson (1867-1950,) US Secretary of War, 1940-1945, was de facto head of the Manhattan Project. This poem is loosely based on an event from Stimson’s life.]

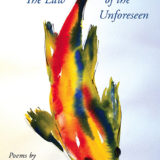

Praise from the back of the book –

In The Law of the Unforeseen, the law Harkness speaks of requires us to know now and then. We walk under “the trees of unremembrance,” so that we may know who we are, how we got here, and who we came from. And we arrive in this lovely and threatened paradise called Earth, right now. The “endless replication of clam shells, ants, / hyacinths in spring”?—it’s true, we will lose those things, individually, but these poems savor such stuff, and in that savoring they give us hope for the future. –Robert Wrigley, author of Box and The Anatomy of Melancholy

Ed Harkness’s great gift is for the lyric telling of “the heart’s winding chronicle.” Permeated with the keenly felt ache of life, “the world breaking your heart and, somehow, mending it,” these poems celebrate the sensuous beauty of “this gold world” in deep music line by line. Harkness’s poems are a necessary sustenance for our present perilous moment. -Alicia Hokanson, Author of Mapping the Distance

Ed Harkness’ poems are always raising themselves up, always lifting off the ordinary. They are persistent, observant, sharply etched, hovering in the vicinity like mist off the woods and waters, invisibly stirring the clear air, offering unlikely gifts we might suffer from the lack of otherwise. -Paul Hunter, author of Clownery

Suffused with tenderness for the earth and its fragile creatures, The Law of the Unforeseen contains poems—lyrical, sensual, often comic, sometimes savagely funny—that ride a current of melancholy, a certainty of loss which deepens the vitality Harkness brings to the page. This is a rich, generous-hearted collection, a moving testament by a man of passionate conscience. -Anne Pitkin, author of Winter Arguments

In The Law of the Unforeseen, Edward Harkness confronts the living world as urgently as the world of ugly vase, thrift-store spoon, broken, half-buried beach shell, and the “floral design of pond ice.” The embrace of this important collection is truly Whitmanesque. I deeply admire how it keeps breaking me even as it pulls me toward its heart where every bloodied instant lives alongside some unlikely bit of mending. -Derek Sheffield, author of Through the Second Skin

Russell Hill –

I…can’t settle on a favorite poem. ‘The Poetry Class’ — In my teaching career (50 years of high school English) I had students like that. She reminded me of a boy who showed up for first period, hair wet, often late. He lived in Muir Beach, a small cluster of houses on a bluff north of the Golden Gate.Muir Beach itself was small, surrounded by jagged rocks, cliffs and heavy surf.He was late because he was surfing each morning. In the dark. He went out on his board in the blackness and surfed in toward that tiny beach.I asked him how he avoided the rocks.“I listen,” he said. “I can tell the difference between the sound of surf on the rocks and ones on the beach.” It was an Advanced Placement class, and he often took off in a different direction in an essay.I reminded him that he would not pass the AP exam doing that. “No,” he said. “But I thought I saw something more interesting.” And he was right. He would not pass the AP exam and it didn’t bother him. Anyone who would surf in the blackness, listening to steer himself from life-threatening rocks was on a different wave length than my other students, who were there because they wanted desperately to pass with a high score and get into a good college. I have no idea what happened to him. But like that girl who stood in the hall, he marched to a different drummer. When the traditional essay format didn’t suit what he was doing, he veered off in a different direction.It must have been like listening to the surf in the darkness.

“The Axe” is as perfect a microcosm of our history as I have seen.You managed, in those three short chapters, to encompass immigration, a war and the history of the plains. And the history of the man who lived that arc.

Once, on a late afternoon in Iowa City, a bat suddenly clung to my shirt. In a panic I brushed it off. I thought of Theodore Roethke’s line, “something is amiss or out of place when a mouse with wings can wear a human face.” And your poem, “Bat in Daylight” resonated with me.

Something else that resonated: you write of your ancestors leaving the coal mines of Cornwall, ending up in Iowa. My ancestors came from the coal mines of Wales and the arsenic mines of Devon and ended up in the coal mines of Spring Valley, Illinois. In one letter to his wife a great-grandfather wrote, “it’s good to see men coming out of the ground again.” My father and his two brothers were the first men of the family that did no go down into the mine.My father taught woodshop in Spring Valley, and told of young men who came up out of the mine in September to play football for the high school, only to return to the blackness when the season was over.

The Law of the Unforeseen is a brilliant collection. I, too, have been at the House of Mystery just south of Garberville. I think in these poems, that you have opened the yellow door.

David Long –

The Law of the Unforeseen

Edward Harkness

[Pleasure Boat Studio, 2018]

by David Long

My first day in Richard Hugo’s workshop, forty-some years ago, Hugo asked a second-year student to read his poem. “Robbie Loftus has beaten me up again in the boys can,” it began.

Wow, I thought, you can do that? I loved the voice. I loved that it named names, that I heard it talking to me. I loved the attitude behind the voice, the aplomb, the it is what it is quality when faced with the indignities of youth. I loved that by the first line it had me smiling. Thus, my introduction to Ed Harkness. Later that year, Hugo gushed over another Harkness poem (“The Man in the Recreation Room”); that it was formal, a villanelle, struck me as really odd. Only later did I understand how the mixing of these two impulses, the informal and the formal, gave his work its particular character.

One nugget of Hugo wisdom I still wholeheartedly endorse is that memorable writing has two subjects: the thing that snags your attention in the first place, and the thing you discover as you write—the true subject, the surprise, the thing you didn’t already know. The Law of the Unforeseen is a marvelous example of this dictum. As in his earlier collections [Saying the Necessary (2000), Beautiful Passing Lives (2010), and several chapbooks], these poems concern themselves, outwardly, with family life, and the natural world of the Pacific Northwest (he has a special affinity for birds). But they’re never static, they keep cranking things another crank.

Throughout The Law of the Unforeseen there’s an urgent sense of the poem as an act of revolt against the effects of time. There are elegies for departed friends, and a heartbreaking, regret-fueled account of a poetry student murdered by her boyfriend. Increasingly, the stories he wants to dig up and preserve are those of his own ancestors. In “Photo of the Twins, Ca. 1897,” we meet the Savoy girls, Mert and Gert, their girlhood portrait colliding with what’s known of their later history. The urge to know them (and be known by them) is potent: “I want to think my kinswomen . . . would smile,” he writes, “or at least have understood . . .

my life’s work, which has been to rouse them,

raise them from their graves, to light the flash

that saves them, and saves the unsmiling

radiant world, against all odds, from oblivion.

In “Ax,” Thomas Harkness, immigrant from County Antrim, fibs his way into the Union Army at age 55; three months later, a ricocheting ax blade slices through his shoe and four inches of bone and tendon. As with the twins, we flash ahead to glimpse his later life, and finally his broken grave marker; the poem ends:

The ax has gone to rust, just as his stone

will fall away to pieces, chunks, gravel, grit,

and at last to dust, its inscription

reduced to a whisper in the elms.

Another poem starts with a hand-made wooden spoon from a thrift store—burn-scarred, its wear suggesting years of stirring by a left-handed woman . . .

perhaps living—wild surmise—

in Iowa in the thirties, baby

balanced on her right hip . . .

The “wild surmise” fills another eight stanzas—his capacity for empathy and his powers of invention both have hair-triggers, we learn.

The Law of the Unforeseen has no villanelles, but there’s constant attention to sound and design, line and stanza pattern. Tellingly, “New Year’s Eve,” the most harrowing of poems (recounting an adult son’s fatal heart attack and “one chance in a million” resuscitation) uses a fixed form with key words repeated. And there are a number of sonnets, “Coffee” and “The Lesson,” to name two, both powerful, both reminding me that a rhymed couplet can hit like a mallet.

For all the grace and accessibility and humor (he can be savagely funny), Harkness also possesses a vein of rock-hard moral outrage. It surfaced throughout the earlier collections —in “Spain, 1938” (Saying the Necessary), for instance, and in the remarkable sequence, “Five Angry Little Songs” (Beautiful Passing Lives). He loathes war, duplicitous government, faux patriotism, stupidity, untruth, and all the rest of it. In another of the new sonnets (“America, Great Once Again”) we watch a ten-year-old girl witnessing her mother’s beating by police:

. . . men

in body armor, one boot on the woman’s back,.

one on her neck, while others tie her wrists,

twisting them till she shrieks, her body slack

from writhing against what it resists.

The devastating “The Unfocused Eyes of Drones” begins benignly enough:

They’re dream wrens in the clear lake of day,

like toys, a slightly larger replica

of those model planes men play with

at the park on weekend to escape the house.

However (calling to mind Hannah Arendt’s phrase “the banality of evil”), it soon morphs into an account of a drone operator, somewhere in the American Heartland, dispassionately annihilating a target on the far side of the world—including the girl in red headscarf watering eggplants in the courtyard outside her home. Like you, perhaps, I’ve been profoundly demoralized by the 45th presidency; chilling as a poem like “The Unfocused Eyes of Drones” is, I find myself somehow bucked up, heartened by the sound of defiance; I’m reminded how critical it is for our artists to remain engaged.

Finally, The Law of the Unforeseen is a collection to celebrate, a book with range and heart, the product of intense curiosity and love of craft. If Hugo were still around he’d still be gushing.

❖

Sibyl James, author of 12 books of poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction –

ver a quarter of a century ago, Ed Harkness and I were teaching in China. One day in Tianjin, we rode our bikes through the street markets, shopping for bread, the air so thick with winter coal-stove soot that when we wiped our faces the cloth turned black. In the poems of The Law of the Unforeseen, Ed is still showing that enthusiasm for entering whole heartedly into whatever life he finds around him, even if it tarnishes his skin and threatens his lungs.

It could be small things: the three Italian prunes that rolled off his desk, “bruised and bleeding now,” or roses “fallen, one brown petal after another, / like burnt potato chips on the lawn,” or “the smooth-as-a-baby’s-butt / slides from the 3rd fret to the 5th” in a tune by Mississippi John Hurt. What Harkness does is make those small things matter.

And the bigger ones. The “rattling emphysemic rasp” of a workmate, “asking would I be so kind as to spot him a Big Mac.” The poet’s father mowing the lawn, “straining, muttering, wrestling the mower’s wooden / handles like a man who’s had it, who knows futility / and puts his whole being into its resistance.” The woman of the poet’s imagination whose thrift store spoon “contains all the sadness of her left hand.”

The collection is divided into six parts, each named after one of the poems it contains, while the other pieces in that section take up, subtly and sometimes tangentially, certain themes, images, or feelings from the title poem. “Airborne” illustrates the imaginative range of perspectives gathered under the section’s title. There are poems about “the plunge and rise” of swinging, a meadowlark, a balletic bat, girls jumping rope, and Walt Whitman tossing notebook pages in the air where “they rise like gulls.” In one poem, the poet remembers his child self “flung from the jackknifed / tractor about to roll.” In another, a neighbor flies a model plane while a military man somewhere in the U.S. remotely directs his drone to kill a foreign girl whose water bottle “could in his mind be a bomb.”

Maybe what strikes me most about this collection is not only its ability to enter so empathetically into both the joys and the sorrows of all creatures, but to insist on the power of just keeping on keeping on in the face of despair about the current condition of our war-ridden, climate-threatened, frustrating world. When I mentioned this to Ed, he pointed out how poets believe so strongly in the power of words to save us. That belief crops up often in these poems.

I like poetry reviews that include large chunks of the poems, so I’ll end this one with the “chunk” that concludes the book, where Harkness most explicitly reveals his belief in words to encourage us to keep on:

If we knew the words we might keep the world,

its rivers, its ice, its bitterroot, its winter wrens,

its hemlocks, its moonlight, its children,

its Shakespeare, its Szymborkska, its rosehips,

its green and orange lichens, its Dylan,

its kora players, its hummingbirds, you,

me, and our Muslim neighbor, Maya, alive.

Read poetry by Edward Harkness appearing in Terrain.org: “Union Creek in Winter,” a Letter to America poem that includes the lines referenced above; two poems selected by Robert Wrigley as the winner of the Terrain.org 8th Annual Poetry Contest; and two other poems. – by Sibyl James, author of 12 books of poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction, including most recently The Grand Piano Range and Hard Goods & Hot Platters. She has taught in the U.S., China, Mexico, and—as Fulbright professor—Tunisia and Cote d’Ivoire.