Description

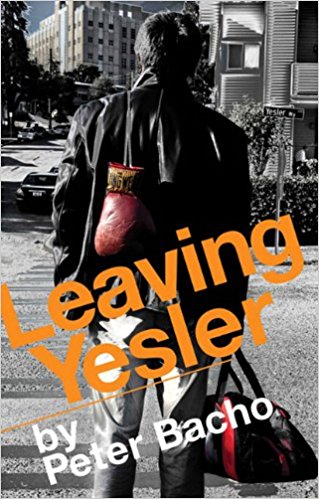

Fiction. Filipino American Studies. Latino/Latina Studies. African American Studies. Young Adult Fiction. Bobby’s life is difficult—in short order, he lost his mom to cancer and his older protective brother to Vietnam. His Filipino stepfather is old and not long for the world. The plot, which takes place in the politically tumultuous year of 1968, follows him from his last days in the Yesler Terrace housing project in Seattle to just short of his first day in college. Not only must he survive the dangers within the projects, he must also come to terms with questions about his ethnic identity and his sexuality. The novel is set within the literary realm of magical realism. The ghosts of Bobby’s mother and older brother continuously reappear to comfort and advise him. It would best be classified as Young Adult, although it is clearly not limited to such an audience. Essentially, this is a coming-of-age novel set in an urban environment, and it deals with serious issues in a young man’s growth and development.

“Leaving Yesler is a fun, engaging read. It’s Bacho’s first attempt to write for a young adult audience. And he succeeds wonderfully, telling a moving coming-of-age story in a relaxed, elegant style, that pulls you into a world of struggle and violence, but also of courage and perseverance—a world where Pinoys fight on despite the odds, and where Bobby Vincente, the hero of the story, eventually learns not to lose sight of what’s worth fighting for…” -Benjamin Pimentel, Inquirer Global Nation

“At some point in Bobby’s life he discovers what the word heroic means even if you find yourself in the wrong war or the wrong neighborhood…” – Shawn Wong

“Author Peter Bacho, a two-time winner of the American Book Award, explores themes of belief/disbelief, arrival/departure, and love/violence, through which he achieves a portrait of embodied strength in his protagonist. Bobby Vincente is sensitive, faithful, and determined not to be defined or limited by anyone other than himself. This struggle takes him to the boxing ring, where his physicality is awakened; to community college, where he studies in hope of passing the GED and avoiding the draft. Out of Bobby’s sexual and emotional growth emerges a great capacity for forgiveness, a penchant for cooking, and a deep commitment to family. Bacho accentuates Bobby’s stressful mental state by making use of a narrative style that is blunt and interrogative. He creates a stream of constant self-definition and re-definition that rides up along the emotional highs of love, success, and pride and down through the lows of rejection, loss, and shame, while also opening the story to a host of literal spirits.” -Patty Comeau, ForeWord Magazine

Peter Bacho has written several books during his career. His nonfiction book Boxing in Black and White (Holt) made the Children’s Center for Books Best Books List in 1999. He has also won an American Book Award (for Cebu, 2006), a Washington Governor’s Writers Award (for A Dark Blue Suit, 1998), and The Murray Morgan Prize (also for A Dark Blue Suit). Cebu was listed as one of the top 100 books written by a University of Washington (affiliated) writer over the past century. Bacho has been praised as a “major voice in contemporary literature” (Tom Howard), with a “strong, steady style” (Kathleen Alcala), and a “disarming…sense of humanity” (Thomas Keneally). Bacho teaches at The Evergreen State College, Tacoma Campus, in Washington State.

Shawn Wong –

Seattle was different then, in a period between cutting down big trees and making airplanes and becoming the affluent coffee and software capital of the world. In Bobby’s time you have to figure out a way out of the world in which you live—do time in Vietnam like his brother, go to college, or simply fight your way up the ladder. At some point in Bobby’s life he discovers what the word heroic means even if you find yourself in the wrong war or the wrong neighborhood. Peter Bacho doesn’t let readers forget what it meant in that in-between-time just before we became what and who we are today, and how a young man learns compassion and humanity.

Patty Comeau, ForeWord Magazine –

Leaving Yesler encounters seventeen year-old Bobby Vincente in the wake of his older brother’s military death; faced with the challenge of caring for his aging father, this young man from urban Seattle’s housing projects is forced to take control of his life and identity as he traverses a period of life-altering change marked by new interests, new challenges, and ultimately, new life. Author Peter Bacho, a two-time winner of the American Book Award, explores themes of belief/disbelief, arrival/departure, and love/violence, through which he achieves a portrait of embodied strength in his protagonist. Bobby Vincente is sensitive, faithful, and determined not to be defined or limited by anyone other than himself. This struggle takes him to the boxing ring, where his physicality is awakened; to community college, where he studies in hope of passing the GED and avoiding the draft. Out of Bobby’s sexual and emotional growth emerges a great capacity for forgiveness, a penchant for cooking, and a deep commitment to family. Bacho accentuates Bobby’s stressful mental state by making use of a narrative style that is blunt and interrogative. He creates a stream of constant self-definition and re-definition that rides up along the emotional highs of love, success, and pride and down through the lows of rejection, loss, and shame, while also opening the story to a host of literal spirits. These ghosts, the majority Bobby’s deceased relatives or neighbours, coax and provoke him to learn more about himself and about the kind of person he wants to be. Paulie Vincente, protector and tormentor of his younger sibling in life, continues to influence his brother by appearing and speaking to him even at the most inopportune moments. Readers will get the sense that there is a mission here, and Bobby’s growth as a character owes a great deal to his flat-out acceptance of these apparitional lessons as a part of a larger reality. Though the novel takes place during the Vietnam War, this tale of a mixed race, impoverished, and soon-to-be orphaned American rings true to a contemporary setting. A critique of organized Christianity also weaves throughout the book that, combined with Bacho’s technique of magical realism and the value placed on self-determination, presents with a strong message of non-conformity. Leaving Yesler is accessible, contains fears and joys to which young people can relate, and offers a great deal to ponder.

Benjamin Pimentel, Inquirer Global Nation –

Filipino-American novelist Peter Bacho’s latest work is partly about ghosts. They’re tough ghosts, street-smart spirits, trying to settle unfinished business. They come from a part of Filipino America that few people, including many Filipino Americans, read about, or even know about. That’s what makes Leaving Yesler an important work….Bacho tells the stories of [Filipino immigrants] children. He is one of them, the son of a manong. Many of his generation came of age in the 1960’s and 1970’s, as America was reeling from the Vietnam War, the civil rights protests, and the identity-based activism that swept through many ethnic and immigrant communities, including Filipinos. Many of these young FilAms led a tough life, as children of working-class Pinoy immigrants. This is the world Bacho portrays….Yesler is a well-known public housing project in Seattle, home to working class people, including many Filipino families….It’s a community where a certain level of toughness is required to survive. It was a world Bacho got to know pretty well in the 50’s and 60’s…The novel’s protagonist, Bobby Vincente, is a mixed race FilAm teenager. He has lost his mother to cancer, and his elder brother to Vietnam. His dad, a Pinoy old-timer and one-time boxing sensation named Antonio, has been struggling to recover from psychological wounds from World War II. In many ways, he is typical of the Pinoys of his generation, the manongs who struck out on their own in America at a time when Filipinos were seen and rejected as outsiders. They were hard-working, tough men. Bacho knew many of them growing up. “My dad was a pretty hard, tough guy,” he says. “But I loved him and admired him even though he was sometimes distant. I knew he did the best he could do, given who he was.” In Leaving Yesler, Bobby is setting out with his dad to move on. And he gets some help from ghosts. One of them is his late older brother, Paulie, who helps Bobby wrestle with issues of identity, their parents past, love, and sex. The fine points of young adulthood. I’ll stop there and not spoil the story. Leaving Yesler is a fun, engaging read. It’s Bacho’s first attempt to write for a young adult audience. And he succeeds wonderfully, telling a moving coming-of-age story in a relaxed, elegant style, that pulls you into a world of struggle and violence, but also of courage and perseverance—a world where Pinoys fight on despite the odds, and where Bobby Vincente, the hero of the story, eventually learns not to lose sight of what’s worth fighting for. This was Bacho’s world. “The war in Vietnam loomed large among young people during his time. He himself almost got drafted….The war screwed up most of my friends, most of whom were draftees or joined up to avoid the draft and negotiate a better deal, he says. Of those Filipino Americans I knew in the Seattle area, about 80 percent were drafted…the Filipino kids then, for the most part, were regarded as not college material, especially in the public schools, which meant they were meat for the draft….We were Pinoys, and we wanted to be like our fathers…and that applied to the guys who were mixed race as well. It was a very powerful culture, in my opinion.” And it’s a culture that he is taking on now in fiction aimed at young people. That’s particularly good news for Filipinos in North America and beyond. There’s such a dearth of material on the Filipino American experience, especially the stories of the children of the manong generation. Bacho, who won the American Book Award for his novel Cebu and who has won praise from other writers such as Thomas Keneally, is doing us a big favor. And fortunately, he’s also having a good time.