Description

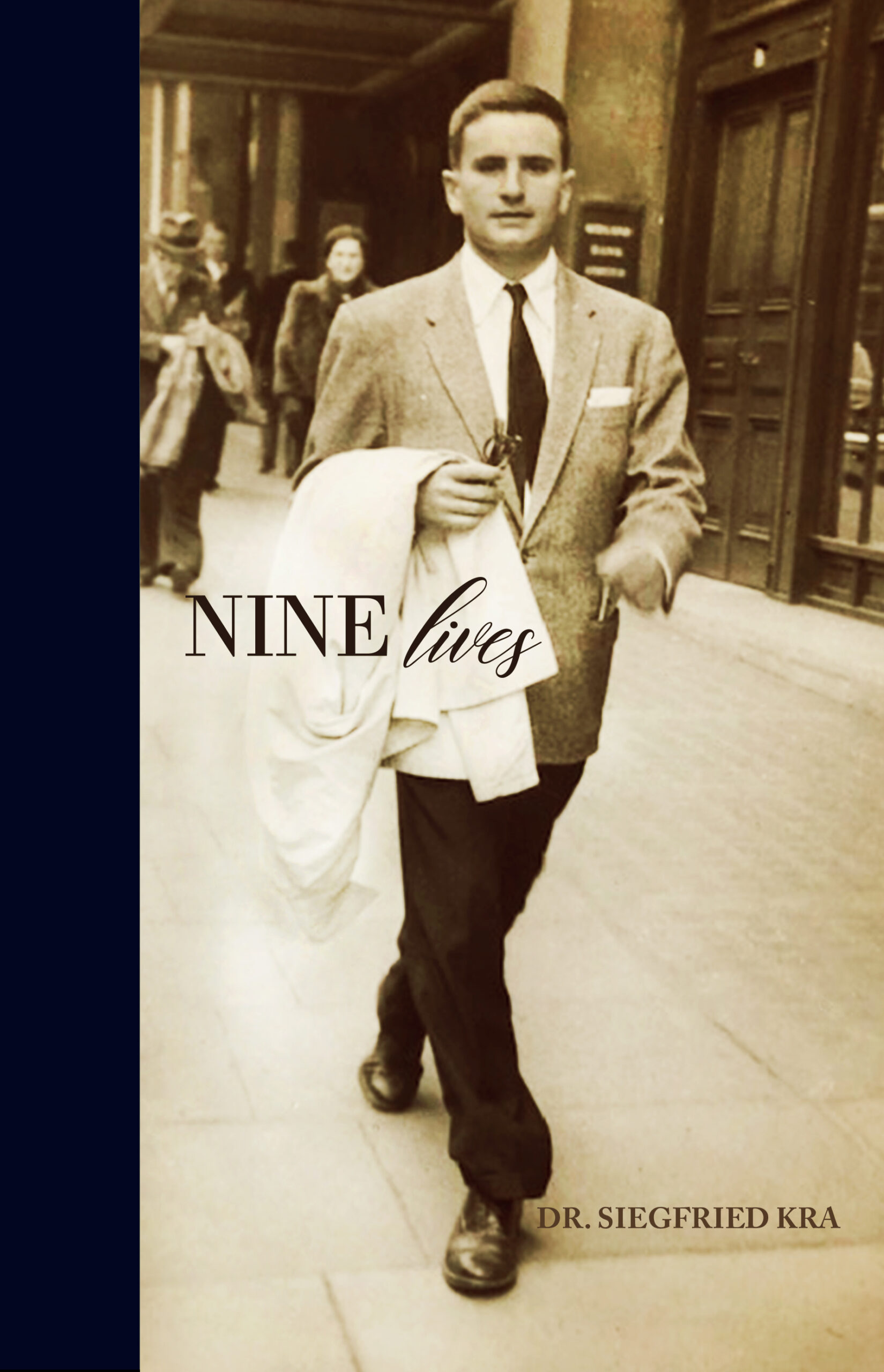

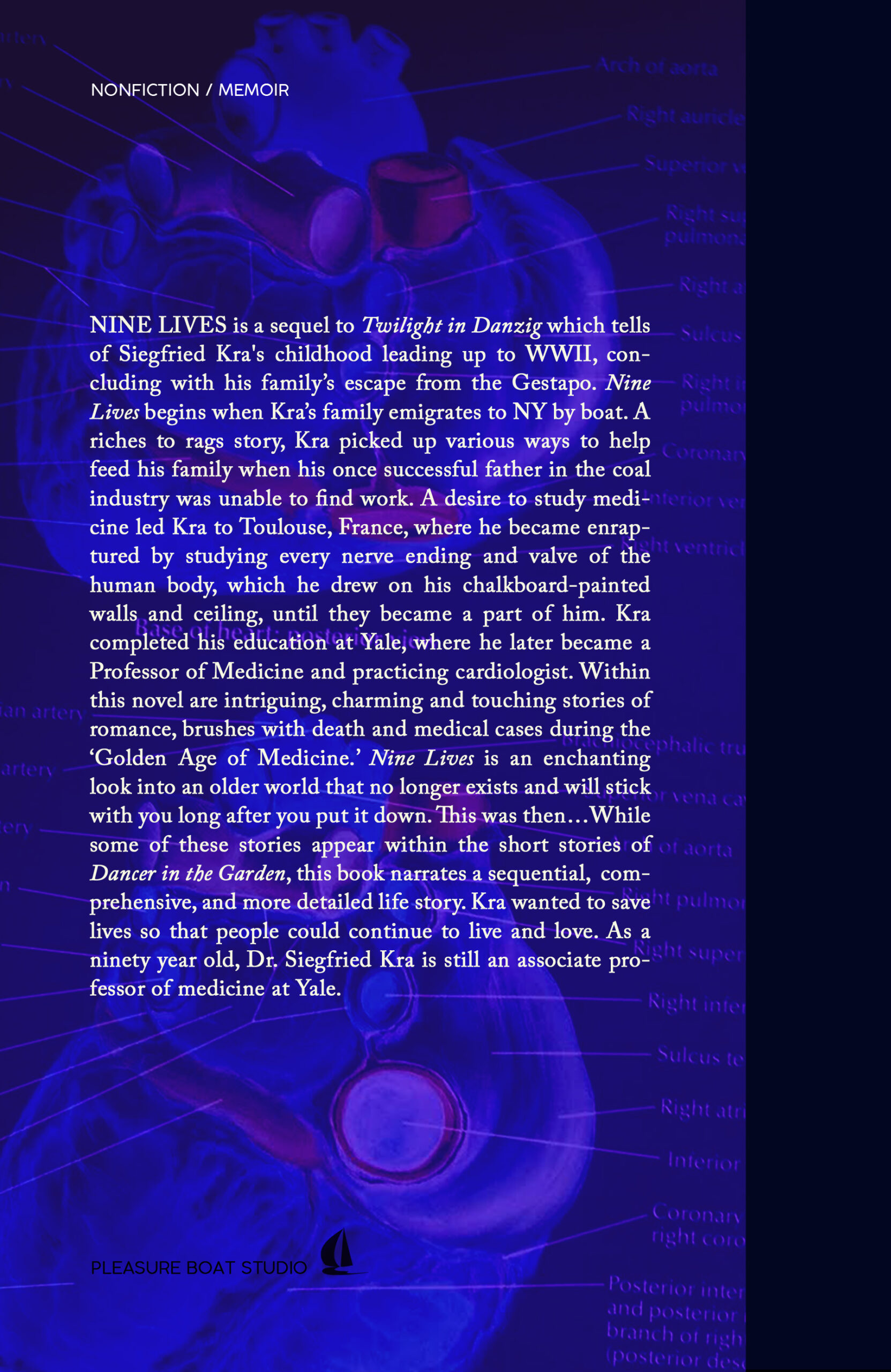

NINE LIVES is the sequel to Twilight in Danzig which tells of Siegfried Kra’s childhood leading up to WWII, concluding with his family’s escape from the Gestapo. Nine Lives begins when Kra’s family emigrates to NY by boat. A riches to rags story, Kra picked up various ways to help feed his family when his once successful father in the coal industry was unable to find work. A desire to study medicine led Kra to Toulouse, France, where he became enraptured by studying every nerve ending and valve of the human body, which he drew on his chalkboard-painted walls and ceiling until they became a part of him. Kra completed his education at Yale, where he later became a Professor of Medicine and practicing cardiologist. Within this novel are intriguing, charming, and touching stories of romance, brushes with death, and medical cases during the ‘Golden Age of Medicine.’ Nine Lives is an enchanting look into an older world that no longer exists and will stick with you long after you put it down. This was then…While some of these stories appear within the short stories of Dancer in the Garden, this book narrates a sequential, comprehensive, and more detailed life story. Kra wanted to save lives so that people could continue to live and love. As a ninety-year-old, Dr. Siegfried Kra is still an associate professor of medicine at Yale and Quinnipiac University Netter School of Medicine.

SIEGFRIED KRA emigrated, with his family, from Danzig, Germany to New York in 1939. He attended CCNY, then went to medical school in France and Switzerland before completing his training at Yale. In his practice as a cardiologist, he has treated tens of thousands of patients. Kra has published over a dozen books, both fiction and non-fiction. In addition to medicine and writing, his passions include opera, growing orchids, and tennis, which he still plays weekly at age eighty-six. He also still teaches as an Associate Professor of Medicine at Yale University School of Medicine and Quinnipiac University Netter School of Medicine. Kra has been an advocate for people, without prejudice for religion, gender, age, race, religion, or politics for his entire medical life. He has been interviewed by CNN, ABC & CBS. For eight years, Kra was on NPR every Thursday from 1982 to 1994, He was on The Regis Show, Religious shows like Club 500, The Smithsonian in Washington, and more, including lectures at libraries in NY.

Review for Nine Lives:

As I reached the last page of Nine Lives, I wondered how the book’s title was meant to be interpreted. The common saying that cats have nine lives could certainly apply to author Siegfried Kra, a man who has escaped death more than a handful of times. But perhaps a more interesting interpretation of the title is the way Dr. Kra’s life has changed so often, so completely, on his path from scrappy kid to accomplished doctor.

Dr. Siegfried Kra is unrecognizable from one chapter to the next, the differences in his life stages made even more stark by the achronological order in which he wrote this memoir. Readers will first meet Dr. Kra in his elegant referral office as he reminisces about the life he and his family had in Danzig, before the Nazis invaded. A moment later, Kra is a young greenhorn in New York, picking up whatever odd jobs he can to support his family. In a flash, Dr. Kra is treating tuberculosis patients in the Swiss Alps. Next thing you know he’s a young teenager helping his mother prepare a hotel for Polish and German refugees from Danzig, and before you can say “cardiology,” he’s an elderly man fighting for his life in a hospital.

Kra is a natural storyteller and an obvious contender for most interesting man in the world. He effortlessly delivers his life story in a series of vignettes, some of which are many pages long while others are only a handful of words. It gives the book a wonderful train-of-thought vibe, as if Kra can’t make up his mind which part is his favorite. Each chapter is shared with such unabashed honestly and romantic nostalgia that I sometimes felt like the author was talking to me directly over coffee and cake. These personal, intimate moments—some of which read almost like unintentional slips—were among the best parts of the book…I greatly enjoyed my time with Dr. Siegfried Kra. Even during the darkest moments, the author’s rapier wit and good humor made every word captivating. Anyone who enjoys a good story will find something to love in Nine Lives.

Review for DANCER IN THE GARDEN:

“…his delightful little collection of true stories from his long life and medical practice. Kra came to America in 1938 as a boy when his family fled the Nazis. After working his way through CCNY, he found himself blackballed by U.S. med schools in the 1950s because he’d been marked as an agitator, so he went to Europe to study medicine in France and Switzerland. One of the best and most moving pieces here dates back to his med student days in Switzerland, where he lost his heart to a beautiful young dancer, a TB patient in a sanatorium high in the Swiss Alps… As a cardiologist, Kra tells us in his Preface: “I take care of people’s hearts so they can go on loving. I can think of no greater privilege.” Judging from his long career, I suspect Siegfried Kra must have been a damn good doctor. And, after reading DANCER IN THE GARDEN, I know he’s a good storyteller too. Kudos to Pleasure Boat Studio publisher for printing this lively collection. Very highly recommended. -Tim Bazzett, author of the memoir, BOOKLOVER

Reviews for TWILIGHT IN DANZIG:

The story of this family is unique due to the great wealth they had and lost. It adds another dimension to the personal hardships and loss suffered by many at the hands of the Third Reich. No Jew was safe during this period. They finally attempt to leave Danzig and their privileged life. It is a very personal story and one that recounts the hopelessness of coping in a world controlled by a treacherous leader. I highly recommend this book. If you don’t read it you are missing a treasure. -Gary A. Wilson, Ph.D.

…a stunning portrait of a city under siege at the birth of the Nazi regime in 1932 and 1933. -Rick Zitter

EXCERPT:

The Plane Crash

The morning was gray and dreary. I was making arrangements for a trip to Boston and upstate New York as part of a lecture publicity tour for my recently published book. All morning I felt uneasy, restless, and exhausted. I was peculiarly reluctant to leave. Perhaps it was the comfort of Sunday morning, surrounded by my chatty, cheerful family at the breakfast table.

I had been booked to leave from the New Haven airport at six that evening, but I had an 8:00 a.m. TV show to do. I decided to leave earlier and arrive in Boston in time to settle in before bedtime. I thought of canceling. I told my wife that I was worn out.

“I am coming down with a virus,” I said. “My stomach feels upset.”

“You really love to go on these tours,” she said reassuringly. “You’ll see, once you get on that plane and to Boston, you’ll be yourself again. And in the morning, in front of the cameras, you’ll be on a high—you’re a born ham.”

She was right, of course. I always found it exhilarating to be front and center. Even though these tours produced few book sales, I really enjoyed the notoriety. And while they only lasted a few days at a time, they offered a change from my tumultuous medical practice.

The day was unusually warm for the end of February. A slight drizzle started as I arrived at the airport. Waiting to board, I saw a little girl in a blue coat embrace her mother and then run out to the plane. I wondered why anyone would allow such a small child to travel by herself. I embraced my wife and daughter and felt a bit sad, and terribly uneasy. I suddenly wished I had driven to Boston, but then I’d have had to drive to Syracuse and Rochester and Buffalo.

An experienced traveler, I always requested the seat behind the pilot on these small Otter planes. It made me feel more secure. Snaking myself down the narrow aisle, I caught a glimpse of some of my fellow passengers. There was a tall black man. A mother and her son were in the seat opposite. The little girl in the blue coat sat next to a young man at the back of the plane. There were twelve passengers on this fully booked flight. My raincoat was on my lap, as was my briefcase, which contained a new manuscript I was working on.

Once we were airborne I spread the manuscript on my lap. From the window, I could see New Haven Harbor, covered by an eerie-looking mist. There were two pilots. One was giving the usual in-flight instructions to the passengers, which were terribly garbled because of a defective PA system.

I wondered why pilots were always so tall and strong-looking, and charming. They gave me confidence and trust, making these small commuter planes seem somehow more substantial.

“Well folks, we should arrive in Boston in forty-five minutes,” the senior pilot informed us cheerfully just as the windshield began being pelted with rain. I placed the manuscript pages back into their folder, returned it to my briefcase, and sat back, trying to relax.

I tried to plan what I was going to say on this next interview. But instead, I began to wonder if I would die in a plane crash. I had been fortunate so far, having traveled hundreds of times without mishap. But what if the odds were turning against me?

My own death had not really preoccupied me until then, although as a cardiologist death was my constant companion. How many times had I stood by a bedside and witnessed the last moments of a human life? Everyone dies the same way, unlike births, which are all different. The last gasp of life is a universal phenomenon, regardless of the cause. Death is the end of a personality. Being a custodian of human lives, I was programmed to save them. This was as much a part of my brain as eating and sleeping. But who would try to save me when the time came? Who saves the doctor?

I took a comb from my jacket pocket and began to straighten my hair, arrange my tie, smooth the blazer I was wearing as if I were grooming for a party.

My eyes were transfixed by the windshield. The wipers were moving, large, thin blades that looked like long spider legs gliding back and forth, back and forth, across the glass. How could the pilots see through all the fog and mist? Then I realized that they were flying by the instruments before them.

Suddenly the wipers stopped moving in the middle of the windshield, like a movie that abruptly freezes a frame of the action. In seconds ice formed on the glass, and I saw the pilots’ strained looks as they started pulling and pushing different levers. One of the pilots stretched out his arms. Did anyone else sense that terror was about to strike? The woman behind who was about my age? The little girl? The secretive German traveler, who held onto his briefcase as if all his valuables were inside?

First came a faint odor, almost imperceptible, but somehow familiar to me. It was not disagreeable. It began to grow until I recognized an unmistakable smell I met each day in my office, in the hospital, in the operating room: alcohol. Behind me, the passengers remained oblivious, comfortable, safe.

A little puff of smoke started to curl around the cockpit, slowly increasing, and in minutes the entire cockpit was hidden behind a thick blue miasma. The smoke made my breathing more and more labored, as if I were submerged under water. The passengers began to stir. Sleepy eyes now stared in disbelief and fear. Voices grew louder, “What the hell is going on?” Seconds later little bursts of flame appeared from the instrument panel, fire being spit by a dragon. The fire spread, licking the walls, the cockpit. I threw my raincoat at the fire. It was ablaze in seconds. The smoke increased. I began to gasp for air. I sat back and waited. We would not survive much longer without fresh air.

I wondered if this was what my family felt in their final moments in the concentration camp in Treblinka? The Germans didn’t get me, but the gods would finally have their way. I wouldn’t get to see my children married or write that great novel. The cabin had grown hot, dark, suffocating.

“How long can you withstand low-oxygen concentration in the blood before brain damage occurs?” my professor had asked on the final exam.

Someone shouted, “Where is the fire extinguisher?” and grabbed my tennis racket. This was a pressurized plane. We can’t break a window, I thought. We mustn’t. But someone did, smashing at the glass until it gave. The pilots were festooned in flames, but one of the ghastly figures stuck his head out the smashed window as the plane dove at a steep angle, shuddering and rattling. Death was upon us. I could see mountains, ice-covered mountains.

I’m in Switzerland again, in the very attic where I lived as a medical school student, I thought. There is no heat or hot water in my room, just a little electric stove, and it is a frigid winter. There is a small bed and desk, my open books upon it. Next door lives Klaus, also a student. On his desk are pictures of his father standing next to Hitler.

“Were you in the war, Klaus?” I asked.

“Yes,” Klaus answered in German. “I was in the submarine service. I knew nothing of what went on. My father was Hitler’s friend, a close friend.”

Klaus and I often shared coffee and exchanged notes. One morning he was found dead, having jumped from the bridge in the center of town.

Suddenly the mountains were covered with a blinding bright yellow light. I squinted to see. I heard soft voices. It is so peaceful, the most peaceful moment of my entire life, absolute serenity. I am floating above the plane, an objective observer calmly watching it burn.

I must have passed out—or had I died? The plane was on the ground. I unfastened my seatbelt, moved my arms and legs. There was no pain anywhere, only heat and stifling smoke. I lurched out of my seat. There was moaning and screaming, the sounds of disaster, as I tried to run to the back of the plane. The exit door was blocked. I cleared it, then kicked it until it flew open. A tall man standing behind me dove out of the open door like a swimmer diving into a pool. Lying at his feet was the little girl with the blue coat, shrieking. Her face was covered with blood. I grabbed her by her coat and dragged her out with me. The ground was hard and icy cold. It must have snowed. I dragged the girl along the ice, away from the blazing plane.

“Stop pulling me,” she screamed, “you are hurting my back!”

“Everything is okay, you’re fine,” I said, the doctor in him speaking. But the passenger in me was terrified.

Suddenly one of the pilots appeared, black as charcoal, weaving from side to side as if drunk. His leg was ripped and bleeding.

“Get away from the plane!” someone shouted. Passengers were crawling, staggering away. The little girl in the blue coat stood and walked. A young woman, arms outstretched before her, was feeling her way.

“I can’t see!” she screamed.

I took her arm and escorted her away from the inferno. Her face was wet and red, her eyes swollen shut. We moved slowly, a grotesque march from hell. Now a terrible explosion, as if planets had collided. Then an ugly pile of acrid-smelling, burning debris was all that was left of Pilgrim Flight 458 headed for Boston. That same sense of utter peace I had experienced when the conflagration began, returned. Still I felt no pain, though I knew I’d been injured. There was no numbness. My knee was swollen to the touch, and my ankle looked black. I could feel the warmth from the burning plane. Am I still alive?

The young woman placed her arm in mine. “I’m so scared. Please! I don’t see anything. Where are we?”

“You are fine,” I reassured her. “We are saved. Don’t worry. I’m a doctor. I will take care of you.”

“Are you really a doctor? Oh, thank God! God sent you to me.”

What I had assumed was frozen ground was in fact a lake, a frozen lake on a warm day. Somehow we had to cross this icy surface to safety. I strained my eyes to spot the shore and thought I saw it a long way off. If the ice were to give, the blind girl clutching my arm with all her strength would pull us down, and we would both drown. I could have left her to wander off by herself, to save my own life. I was strong enough to walk to shore. But I had never abandoned a sick person in my life, and surely wouldn’t now.

“We have to walk very carefully,” I told her softly. “We’re on a frozen lake, but the ice seems spongy, wet. Walk carefully, step carefully.”

Her grip on me grew tighter. She took small steps, brought her feet down daintily, as if she were walking on eggs.

“Just pretend that we are walking in the park on a nice fall day and that everything is safe and beautiful,” I said softly. “We are lucky to have survived the plane crash. You will tell your grandchildren of that one day.”

Our stroll continued, like two lovers arm in arm. Each step could mean the end of us both. I felt the patches of soft ice move slightly below my feet, but the lake remained frozen despite the warm air. The plane, we were later told, had crashed right in the center of the frozen lake. I never felt the impact. The plane slid and sailed a thousand feet across the ice before the nose gently dipped into the lake, a huge bird taking a drink. One of the wings of the plane had broken off and lay flat on the ice, smoldering. I watched it slowly begin to sink and disappear below the surface. I didn’t tell my blind escort what was happening, but she heard the terrifying hiss it made and the swishing sound as the reluctant wing was drawn to its icy grave.

“What was that?” she asked in panic.

“It’s the wind, nothing more. We’ll be on the shore soon. We’ll be safe.”

Now I could clearly see the shore. On the banks of this lake of death were some young boys, standing, watching, but no one else to help.

“Walk towards the other edge!” they yelled. “It is all melted here.”

We changed our course like mariners sailing the dark sea. Now I saw that others had already reached land and were urging us on. We approached shore, and the ice became soft as pudding. It reminded me of how I once crossed the streets in New York as a child. First stepping on the ice on the edge of the sidewalk and then suddenly being in water, slush.

Three young boys came to the very edge of the lake with their arms outstretched. We were entering water now. The young woman clutched me ever more tightly as, with each step, we began to sink. The icy water reached my thigh. It felt like hot moss. One more step. Safety was five feet away. I threw her with all my strength, and the three boys grabbed her by the arm, pulled her out. I struggled to get to land, the water now almost reaching my shoulder. Another step. Another. The boys had me. A mighty pull.

Soaking wet, I began to feel terribly cold. We walked, the three boys leading us through thick vines. Surely this must be a beautiful spot in the spring: yellow forsythia in full bloom, framing the lake. They we climbed over a barbed-wire fence.

“Just pretend that we are walking in the park on a nice fall day and that everything is safe and beautiful,” I said softly. “We are lucky to have survived the plane crash. You will tell your grandchildren of that one day,” I repeated.

*

“Doctor, you must sign in and be examined. You just survived a plane crash!” the nurse shouted.

I gave her a derisive smile, and said, “All I want is a hamburger. I haven’t had one in years, since I’ve been on a damned low-cholesterol diet.”

I was hungry. Famished. I felt as if I hadn’t eaten in weeks. The adrenaline was overflowing. I ate three hamburgers and then called my wife.

“Don’t get worried, you probably heard of the crash. If you didn’t, turn on the radio. Come and get me. Bring a coat, a hat, and a bottle of scotch.”

When my wife and daughter arrived I was lying on a stretcher being examined by an intern. They did not know what to expect, and both burst into tears of joy when they saw that I was in one piece. Much to the dismay of the emergency-room staff, I grabbed the scotch and drank to my heart’s content. My knee was injured, but I refused to stay in the hospital. As I was leaving the emergency room, a friend who was an actor in the Yale Repertory Theater approached to thank me for pulling his daughter off the plane. The little girl in the blue coat.

*

The press swarmed, vultures lusting to hear from me about the crash, especially because I was a doctor.

So I did get my day on TV, my publicity tour, and the coverage was better than my publishers ever dreamed. Coast to coast, on every network, in the morning, at night, I was interviewed and quoted.

*

I took a long-overdue vacation from my practice. My knee was badly injured, and I limped around in an Ace bandage. I consulted a physician, who prescribed painkillers, which I threw away. I had one physical therapy session. What I needed most, and did not receive from the medical profession, was a kind word of understanding. Instead, one doctor said, “You will be disabled for several months, and don’t be disappointed if you can’t play tennis again. Swimming is much better for you anyhow. You’re getting too old to play tennis. You should know all this, being a cardiologist.”

Tennis had been one of his grand pleasures in life. My tennis racquet had even saved our lives when one of the passengers, an off-duty flight engineer, used it to break the windows of the plane. Who else would have thought of breaking windows in flight?

Doctors feel uncomfortable treating other doctors, and I resented their cold approach. I consulted a neurologist to be certain I had no neurological damage to my brain. But doctors feel uncomfortable being treated by other doctors, too. I was too embarrassed to tell them that during the height of the crash I had seen that bright light that many people describe in near-death experiences. One of my colleagues checked out my cardiovascular system and declared it normal. Yet I did not feel normal. I felt separated from the world, a visitor, an observer.

Once my father had given me boxing lessons, and then I had been matched up against another boy. I had been beaten up miserably and had staggered out of the ring, dazed. That is how I felt for weeks after the crash. Yet I also felt docile, peaceful.

“How is it possible,” the federal investigator asked me, “that you did not get one burn on your body when you were sitting immediately behind the flaming cockpit? The woman who sat behind you was burned to death. It took days to identify her body.” These were among many unanswerable questions that unnerved me. Why had the reservoir been frozen? It had not frozen over for as long as the natives in the area could recall. And why did I have such a strong premonition of danger that day? I was not given to superstitious feelings.

Two passengers on that plane died. I was a scientist and had difficulty accepting that any master plan for my survival existed in heaven. The rabbi of my synagogue said that he I been tested.

“God had too many other agendas to be concentrating on me,” I told the rabbi.

But for his great and sincere concern, I contributed to the synagogue—and to the church too. Just in case.

Ben Haskett, Manhattan Book Review –

Star Rating: 4 / 5

As I reached the last page of Nine Lives, I wondered how the book’s title was meant to be interpreted. The common saying that cats have nine lives could certainly apply to author Siegfried Kra, a man who has escaped death more than a handful of times. But perhaps a more interesting interpretation of the title is the way Dr. Kra’s life has changed so often, so completely, on his path from scrappy kid to accomplished doctor.

Dr. Siegfried Kra is unrecognizable from one chapter to the next, the differences in his life stages made even more stark by the achronological order in which he wrote this memoir. Readers will first meet Dr. Kra in his elegant referral office as he reminisces about the life he and his family had in Danzig, before the Nazis invaded. A moment later, Kra is a young greenhorn in New York, picking up whatever odd jobs he can to support his family. In a flash, Dr. Kra is treating tuberculosis patients in the Swiss Alps. Next thing you know he’s a young teenager helping his mother prepare a hotel for Polish and German refugees from Danzig, and before you can say “cardiology,” he’s an elderly man fighting for his life in a hospital.

Kra is a natural storyteller and an obvious contender for most interesting man in the world. He effortlessly delivers his life story in a series of vignettes, some of which are many pages long while others are only a handful of words. It gives the book a wonderful train-of-thought vibe, as if Kra can’t make up his mind which part is his favorite. Each chapter is shared with such unabashed honestly and romantic nostalgia that I sometimes felt like the author was talking to me directly over coffee and cake. These personal, intimate moments—some of which read almost like unintentional slips—were among the best parts of the book. I would have appreciated something to tie all these vignettes together at the end, something to bring it back around to the passing of Dr. Kra’s father. As it is, the book ends somewhat abruptly and feels more like a shuffled collection of essays than a memoir. Still, I greatly enjoyed my time with Dr. Siegfried Kra. Even during the darkest moments, the author’s rapier wit and good humor made every word captivating. Anyone who enjoys a good story will find something to love in Nine Lives.

Barry Grosskopf –

I enjoyed Nine Lives enough to have read it in a day. The stories were like many in my own life, the boat trip to America, trying to assimilate, resisting bullying, making friends. The medical stories of going to school, the anxiety of absorbing so much information, the temptations which he resisted… I appreciated Dr. Kra’s honesty and openness and want to express how much I enjoyed his book.

Dr. Henry G. Jarecki –

To read the works of Dr. Siegfried Kra is to feel as though you’ve made a new friend, one who is generous and fearless in sharing his life story. Nine Lives, Dr. Kra’s latest “historical novel”, is an episodic collection of vivid memories tracing his family’s escape from fascist Germany, his own coming of age experiences as a refugee, and his ensuing and remarkable life as a physician and citizen of the United States. His peripatetic assortment of romances, accidents, dumb luck and forays into medicine and academics reads as autobiography, but often feels like an adventure film. Nine Lives is ultimately a deeply personal landscape, by turns funny and bittersweet, and always emotionally alive.

Dr. Kra, born in 1930 in Danzig (then the “Free State of Danzig”), has lived in several worlds that are gone forever – pre WWII Europe, with its highly-cultured community of Jewish intellectuals and professionals; New York City during wartime, with its unique mix of striving ethnicities and refugees; post-WWII France, where a young medical student could go to reinvent himself and pursue his professional dreams. All of these iconic locales are brought to life with the warmth and specificity of a great raconteur. In this vein, Dr. Kra is at once rare and entertaining – a cardiac specialist and accomplished academic who comes off like your friendly uncle, engaging the family with his colorful narratives at the dinner table.